Protecting privacy. Preserving progress.

Eyes Off Indiana is a nonpartisan nonprofit advocating for clear, statewide standards for law enforcement's use of Automated License Plate Readers (ALPR) that protect privacy and support effective, accountable policing.

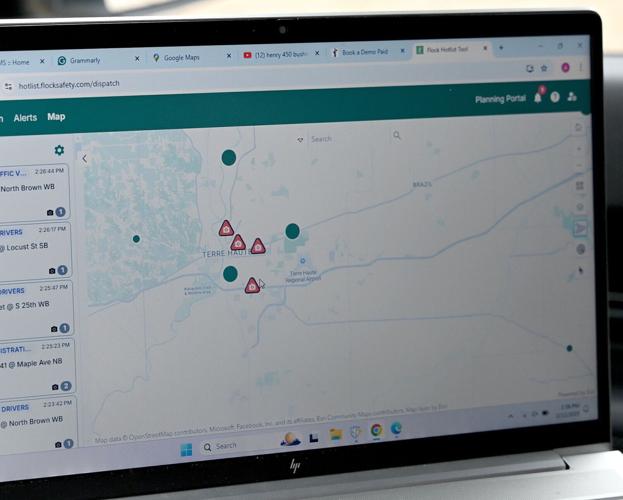

Indiana's ALPR Footprint in Real Time

Total ALPR Cameras Identified

Crowdsourced reports of ALPR units found across Indiana. Actual statewide totals are significantly higher.

Eyes Off Indiana Petition Signatures

The number of Hoosiers calling for clear limits on ALPR data use is growing every day. Add your name here .

Plates Scanned in Indiana Today

Estimated total plates scanned across Indiana so far today.

Data sourced from our partner deflock.me 9 minutes ago

About

Eyes Off Indiana is a nonpartisan nonprofit working to establish clear, statewide limits on automatic license plate reader (ALPR) use in Indiana. We support lawful, effective policing and believe modern tools work best when governed by clear, consistent rules. ALPR systems capture passing license plates and generate location records, yet Indiana has no statewide standards for data retention, sharing, or transparency. Without baseline safeguards, agencies are left to set their own policies, creating uncertainty for officers and the public alike. We study how ALPRs are used, educate the public, and work with state lawmakers to adopt reasonable, enforceable protections that uphold constitutional rights, protect agencies from liability, and preserve ALPRs’ legitimate public-safety value.

The Issue

Indiana lacks clear, constitutional limits on automatic license plate reader (ALPR) surveillance.

No Statewide Regulation on ALPR Use

Indiana has no law regulating automatic license plate readers, leaving each law enforcement agency to set its own policies—or operate without any rules at all.

Unlimited Data Retention

Indiana places no limit on how long police can keep ALPR data. Without mandatory deletion rules, agencies can store years of location records from routine scans, allowing long-term monitoring of citizens’ movements with no oversight or expiration.

Lack of Transparency and Oversight

Indiana has no statewide standards requiring transparency or oversight for ALPR use. Without clear requirements for audit logs, reporting, or review, it is difficult to verify that ALPR systems are used consistently and according to policy, increasing uncertainty for agencies and the public alike.

Policy Goals

Clear guardrails keep ALPR technology constitutional and accountable.

Strict Retention Limits

ALPR data should never be stored indefinitely. Indiana should set firm limits on how long non-relevant scans may be kept, with longer retention allowed only for warrants or active investigations.

Ban Commercial Sharing

License-plate data collected for public safety must remain under public control. Any sale, licensing, or informal sharing with private vendors or brokers should be strictly prohibited.

Transparency and Oversight

Agencies should log all ALPR searches and maintain public portals showing how data is used, shared, and deleted to ensure accountability and constitutional use.

Get Involved

Hoosiers across the state can help keep ALPR technology within constitutional limits.

Become a Community Organizer

Help gather local insight and connect neighbors. Apply for a unique organizer link and early access to policy drafts.

Apply to OrganizeDonate

We accept cash, check, card, and crypto to support outreach, education, and coalition building.

Make a DonationNews

Recent coverage of Eyes Off Indiana and ALPR accountability.

Indiana Economic Digest

As number of license-plate readers surge, more Hoosiers are pushing back

The Herald Bulletin